Alcohol & Dementia

Evidence shows that excessive alcohol consumption increases a person’s risk of developing dementia.

Drinking alcohol in moderation has not been conclusively linked to an increased risk of dementia. If you already drink alcohol within the recommended guidelines, you do not need to stop on the grounds of reducing the risk of dementia.

Despite some claims, drinking alcohol in moderation has not been shown to offer significant protection against developing dementia. So if you do not currently drink alcohol, you should not start as a way to reduce dementia risk.

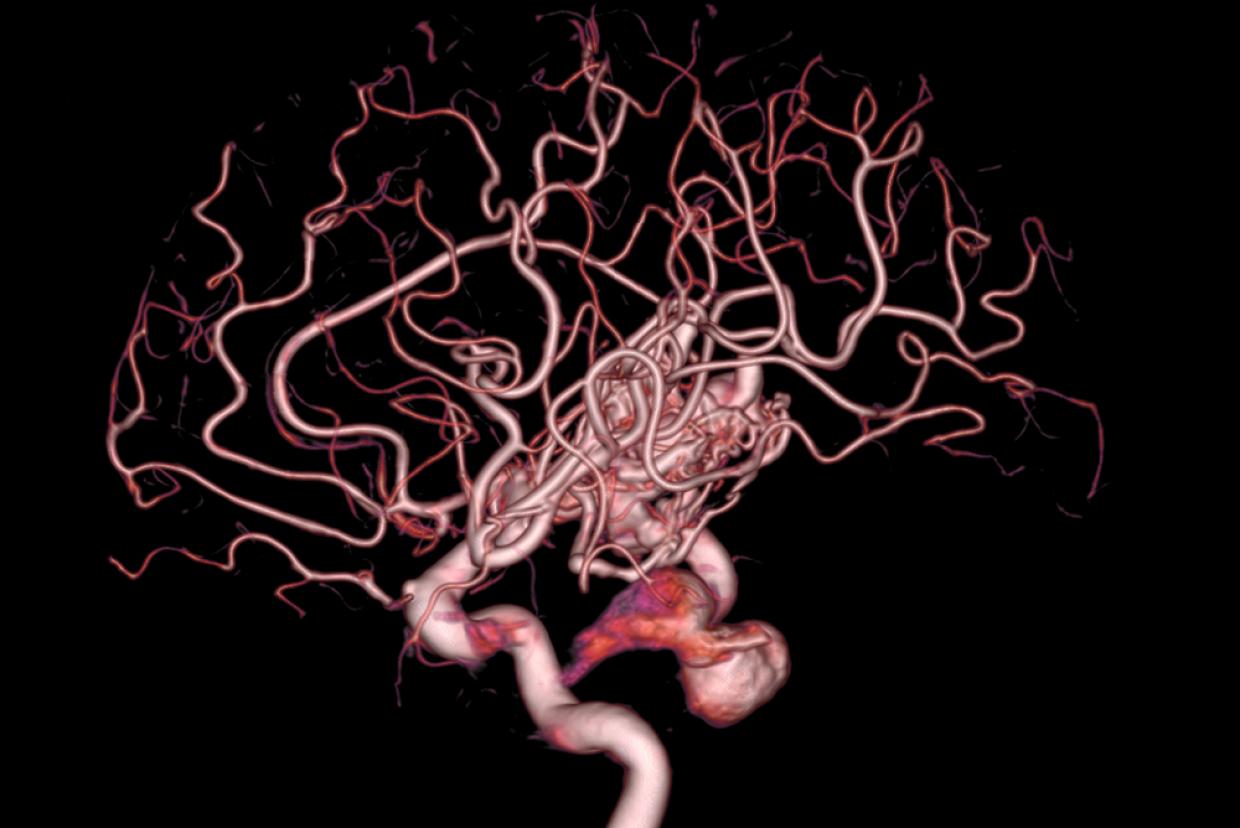

How alcohol can damage the brainDrinking alcohol is linked to reduced volume of the brain's white matter, which helps to transmit signals between different brain regions. This can lead to issues with the way the brain functions. Alcohol consumption above recommended limits (of 14 units per week) over a long period of time may shrink the parts of the brain involved in memory. Drinking more than 28 units per week can lead to a sharper decline in thinking skills as people get older.

Long-term heavy drinking can also result in a lack of vitamin B1 (thiamine) and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome which affects short-term memory.

Alcohol-related brain damage (ARBD) is a brain disorder which covers several different conditions including Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and alcohol-related dementia. It is caused by regularly drinking too much alcohol over several years.

Guidelines for moderate drinking

Current NHS guidelines state that both men and women should limit their intake to 14 units a week. A unit is dependent on the amount of pure alcohol in a given volume and can be calculated for specific drinks.

If you regularly drink much more than this, you are increasing your risk of damage to your brain and other organs, and so increasing your risk of dementia.

Units are based on typical alcohol by volume (ABV) content. However, this does vary. If you’re buying a bottle or can, it’s helpful to check the ABV content on the label.

The NHS basic guideline for units of alcohol is as follows:

- A typical glass (175ml) of (12% ABV) wine: 2 units.

- A large glass of (250ml) of (12% ABV) wine: 3 units.

- A pint of lower (3.6% ABV) alcohol beer or cider: 2 units.

- A pint of higher (5.2% ABV) alcohol beer or cider: 3 units.

- A single shot (25ml ABV) of spirits such as whisky, gin or vodka (40%): 1 unit.

Tips for cutting down on alcohol

If you regularly drink alcohol, try to do so in moderation and within recommended limits.

- Set yourself a weekly alcohol limit and keep track of how much you’re drinking.

- Have several alcohol-free days each week.

- Try low-alcohol or alcohol-free drinks, or smaller sizes of drinks.

- Try to alternate between alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks like cola, water or juice.

- Let your friends and family know that you're cutting down and how they can support you. This can make it easier to drink less, especially at social events.

- Take advantage of particular dates and events to motivate you. For example, you could make a New Year’s resolution to drink less.

Research into alcohol and dementia risk

Several high-profile reviews looked at the research into alcohol and dementia risk. They all found that people who drank heavily or engaged in binge drinking were more likely to develop dementia than those who drank only moderate amounts.

These reviews were included in the World Alzheimer’s Report 2014 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidance. Each combined multiple research studies to reach a consensus on alcohol consumption and the development of dementia.

It is clear that excessive drinking increases a person’s risk of dementia compared with not drinking at all.

NICE Guidelines recommend that alcohol consumption be reduced as much as possible, particularly in mid-life, to minimize the risk of developing age-related conditions such as frailty and dementia.

Moderate drinking and dementia risk

A small number of studies seem to suggest that drinking moderate amounts of alcohol reduces dementia risk compared to not drinking at all.

However, people who do not drink may have given up alcohol after suffering health problems from excessive drinking. These studies don’t separate out the lifetime non-drinkers from those who have quit drinking. Combining both into the same group makes the non-drinking group seem like they had a higher risk of dementia than if lifetime non-drinkers were considered separately.

Drinking even in moderation has also been associated with a reduction in brain volume. Drinking alcohol may be related to other health conditions.