The Progression, Signs and Stages of Dementia

Dementia is progressive. This means signs and symptoms may be relatively mild at first but they get worse with time. Dementia affects everyone differently, however it can be helpful to think of dementia progressing in 'three stages'.

What do we mean by signs and stages of dementia?There are many different types of dementia and all of them are progressive. This means symptoms may be relatively mild at first but they get worse with time, usually over several years. These include problems with memory, thinking, problem-solving or language, and often changes in emotions, perception or behaviour.

As dementia progresses, a person will need more help and, at some point, will need a lot of support with daily living. However, dementia is different for everyone, so it will vary how soon this happens and the type of support needed.

It can be helpful to think of there being three stages of dementia:

These are sometimes called mild, moderate and severe, because this describes how much the symptoms affect a person.

These stages can be used to understand how dementia is likely to change over time, and to help people prepare for the future. The stages also act as a guide to when certain treatments, such as medicines for Alzheimer’s disease, are likely to work best.

How important are the stages of dementia?The stages of dementia are just a guide and there is nothing significant about the number three. Equally, dementia doesn’t follow an exact or certain set of steps that happen in the same way for every person with dementia.

It can be difficult to tell when a person’s dementia has progressed from one stage to another because:

- some symptoms may appear in a different order to the stages described in this factsheet, or not at all

- the stages may overlap – the person may need help with some aspects of everyday life but manage other tasks and activities on their own

- some symptoms, particularly those linked to behaviours, may develop at one stage and then reduce or even disappear later on. Other symptoms, such as memory loss and problems with language and thinking, tend to stay and get worse with time.

It is natural to ask which stage a person is at or what might happen next. But it is more important to focus on the person in the present moment. This includes their needs and how they can live well, and how to help them with this.

For more support on living well with dementia see The dementia guide: living well after diagnosis (for people living with dementia) or Caring for a person with dementia: a practical guide (for carers).

And for more information about treatment and support for the different types of dementia go to the following pages:

- What is Alzheimer’s disease?

- What is vascular dementia?

- What is dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)?

- What is frontotemporal dementia (FTD)?

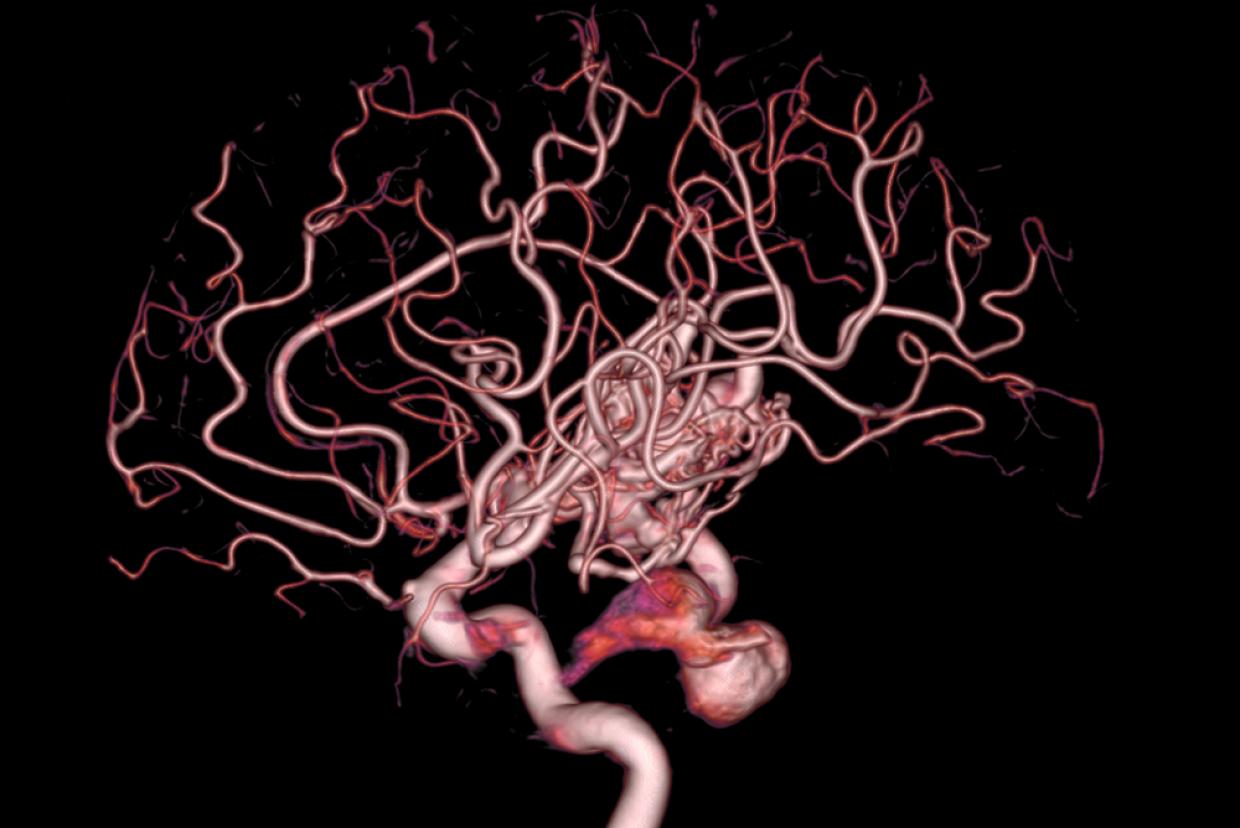

Dementia is not a single condition. It is caused by different physical diseases of the brain, for example Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, DLB and FTD.

In the early stage of all types of dementia only a small part of the brain is damaged. In this stage, a person has fewer symptoms as only the abilities that depend on the damaged part of the brain are affected. These early symptoms are usually relatively minor. This is why ‘mild’ dementia is used as an alternative term for the early stage.

Each type of dementia affects a different area of the brain in the early stages. This is why symptoms vary between the different types. For example, memory loss is common in early-stage Alzheimer’s but is very uncommon in early-stage FTD.

As dementia progresses into the middle and later stages, the symptoms of the different dementia types tend to become more similar. This is because more of the brain is affected as dementia progresses.

Over time, the disease causing the dementia spreads to other parts of the brain. This leads to more symptoms because more of the brain is unable to work properly. At the same time, already-damaged areas of the brain become even more affected, causing symptoms the person already has to get worse.

Eventually most parts of the brain are badly damaged by the disease. This causes major changes in all aspects of memory, thinking, language, emotions and behaviour, as well as physical problems.

How quickly does dementia progress?The speed at which dementia progresses varies a lot from person to person because of factors such as:

- the type of dementia – for example, Alzheimer’s disease tends to progress more slowly than the other types

- a person’s age – for example, Alzheimer’s disease generally progresses more slowly in older people (over 65) than in younger people (under 65)

- other long-term health problems – dementia tends to progress more quickly if the person is living with other conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes or high blood pressure, particularly if these are not well-managed

- delirium – a medical condition that starts suddenly (see ‘What if the person has a sudden change in symptoms?' on this page).

There is no way to be sure how quickly a person’s dementia will progress. Some people with dementia will need support very soon after their diagnosis. In contrast, others will stay independent for several years.

How can a person with dementia keep their abilities for longer?Evidence shows that there are things a person with dementia can do to keep their abilities for longer.

For example, it can be helpful to:

- maintain a positive outlook

- accept support from other people – including friends, family and professionals

- eat and sleep well

- not smoke or drink too much alcohol

- take part in physical, mental and social activity (see 'Physical activity and exercise' for more information).

It is also important for a person with dementia to try to keep healthy by:

- managing any existing health conditions as well as possible

- having regular health check-ups, particularly for their eyes and ears

- asking their GP about jabs – for seasonal flu and pneumococcal infection (that can lead to bronchitis or pneumonia).

This is to prevent new or existing health problems from developing or getting worse. This can make a person’s dementia progress more quickly.

What if the person has a sudden change in symptoms?Not every change in a person’s condition is a symptom of dementia.

If the person’s mental abilities or behaviour changes suddenly over a day or two, they may have developed a separate health problem. For example, a sudden deterioration or change may be a sign that an infection has led to delirium. Or it may suggest that someone has had a stroke.

A stroke is particularly common in some kinds of vascular dementia and may cause the condition to get worse in a series of ‘steps’. When a stroke happens, it causes more damage to the brain which can result in a noticeable decline in the person’s abilities.

In any situation where a person with dementia changes suddenly, or just does not seem themselves, speak to a doctor or nurse as soon as you can.