Can A Healthier Diet Improve Depression?

Mental Health / Healthy DietPoor mental health is a worldwide problem, which has a significant impact on people’s quality of life. Mental health conditions affect around 1 in 6 adults living in England and are more common among women than men. Among these, depression is one of the most common, although the exact cause is often not clear – it may be triggered by a stressful life event (e.g. divorce, bereavement), alcohol or drug abuse, and is more common in people with a family history of the condition.

What is known, however, is that the treatments that are currently available for depression (e.g. anti-depressant medications) are not effective in all cases, and this has led to a lot of interest in other potential therapies, including a healthier diet.

What’s the link between diet and depression?

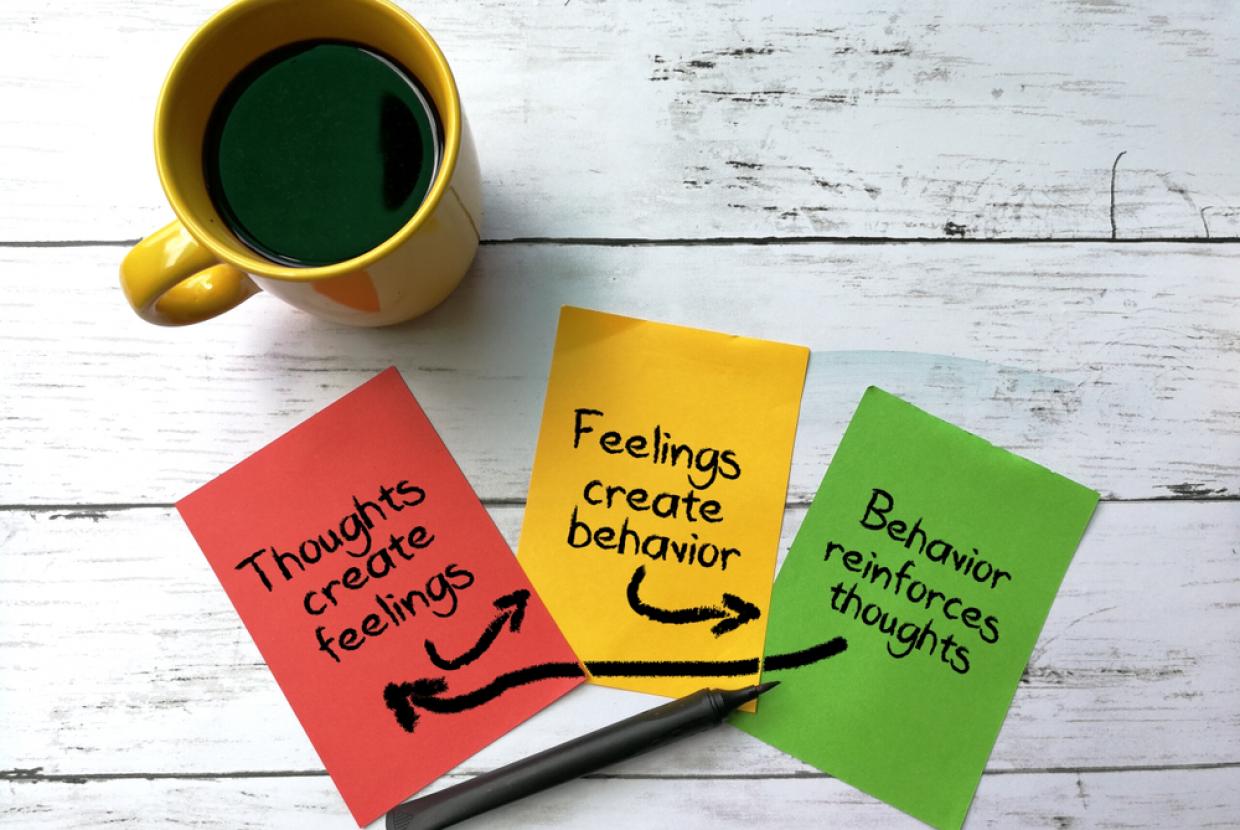

The processes of oxidation and inflammation are recognised for their role in heart disease. However, recent research shows that they may also be involved in depression. We already know that following a healthy dietary pattern like the Mediterranean-style diet, which is rich in vitamins, minerals and fibre, as well as other bioactives, may help in protecting against cardiovascular disease. It is increasingly recognised that the totality of our diet—the combinations and quantities in which foods and nutrients are consumed—may have synergistic and cumulative effects on health and disease, and that it is the overall diet, rather than individual foods and nutrients, that may be the most important. As a result, many researchers have begun to ask: can eating a healthier dietary pattern also help to treat depression?

What is a healthier dietary pattern?

The Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) is perhaps the best studied diet for its beneficial health effects. Although the ‘traditional’ MedDiet may no longer be commonly eaten, the principles of this diet form the cornerstone of many national healthy eating guidelines, including the UK’s Eatwell Guide. These are characterised by:

- higher consumption of vegetables, fruit, wholegrains, seafood, nuts, seeds and pulses

- moderate consumption of dairy

- unsaturated fats as an important fat source e.g. olive oil

- lower intakes of fatty/processed meat, refined grains, sugar-sweetened foods and beverages

- lower salt and lower saturated fat intakes

What is the evidence for dietary patterns and depression?

Most of the research looking at the association between dietary patterns and depression has come from observational studies1. A systematic review of such studies was published last year, including data from 41 studies performed in 8 countries (US, UK, Australia, France, Greece, Spain, Ireland and Iran). The researchers consistently found that following a healthier dietary pattern was associated with a lower risk of depression. This was true not only for the MedDiet, but also for other dietary patterns with similar characteristics such as the Healthy Eating Index and Alternative Healthy Eating Index (HEI/AHEI), as well as the Dietary Inflammatory Index. The problem with observational studies, however, is that it’s not possible to know the direction of the effect – does a better diet protect against depression, or do people with depression eat a less healthy diet?

The only way to really look at cause and effect is through randomised controlled studies. Only a limited number of such trials have been performed to date. In two Australian studies, encouraging depressed participants to eat a more Mediterranean-style diet, either through dietary advice or by providing food hampers and cooking classes, significantly improved their symptoms (compared to a social group control). However, although promising, more studies like this are needed to know if there is a causal link between healthy dietary patterns and a reduced risk of depression.

What are the future challenges for this area of research?

Diet and mental health is a fascinating and rapidly emerging field of research, although one which presents several challenges. Accurately measuring what people eat has always been difficult. Also, symptoms of depression may be either clinically diagnosed or self-reported, and there are a range of different questionnaires that are used to do this.

Despite the limitations, it is possible that dietary recommendations may become more recognised not only for reducing the risk of chronic physical diseases, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer, but also as a way to protect our mental well-being.